SYNOPSIS

''A Clockwork Orange takes place in a futuristic city governed by a repressive, totalitarian super-State. In this society, ordinary citizens have fallen into a passive stupor of complacency, blind to the insidious growth of a rampant, violent youth culture. The protagonist of the story is Alex, a fifteen-year-old boy who narrates in a teenage slang called nadsat, which incorporates elements of Russian and Cockney English. Alex leads a small gang of teenage criminals—Dim, Pete, and Georgie—through the streets, robbing and beating men and raping women. Alex and his friends spend the rest of their time at the Korova Milkbar, an establishment that serves milk laced with drugs, and a bar called the Duke of New York.

Alex begins his narrative from the Korova, where the boys sit around drinking. When Alex and his gang leave the bar, they go on a crime spree that involves mugging, robbery, a gang fight, auto theft, breaking and entering, and rape. The last of these crimes is particularly brutal. The boys travel to the countryside with their stolen car, break into a cottage and beat up the man inside before raping his wife while making him watch. They then head back to the Korova, where they fight with each other. Alex, who loves classical music, becomes angry at Dim when Dim mocks an opera that Alex likes. Alex punches Dim in the face, which prompts the others to turn against their arrogant leader. The next time they go out, they break into an old woman’s house. She calls the police, and before Alex can get away, Dim hits him in the eye with a chain and runs away with the others. The police apprehend Alex and take him to the station, where he later learns that the woman he beat and raped during the earlier robbery has died.

Alex is sentenced to fourteen years in prison. At first, prison is difficult for him. The guards are merciless and oppressive, and several of the other prisoners want to rape him. After a few years, though, prison life becomes easier. He befriends the prison chaplain, who notices Alex’s interest in the Bible. The chaplain lets Alex read in the chapel while listening to classical music, and Alex pores over the Old Testament, delighting in the sex, drinking, and fighting he finds in its pages.

One day, after fighting with and killing a cellmate, Alex is selected as the first candidate for an experimental treatment called Ludovico’s Technique, a form of brainwashing that incorporates associative learning. After being injected with a substance that makes him dreadfully sick, the doctors force Alex to watch exceedingly violent movies. In this way, Alex comes to associate violence with the nausea and headaches he experiences from the shot. The process takes two weeks to complete, after which the mere thought of violence has the power to make Alex ill. As an unintended consequence of the treatment, Alex can no longer enjoy classical music, which he has always associated with violence. This side effect doesn’t bother the State, which considers Alex’s successful treatment a victory for law and order and plans to implement it on a large scale.

After two years in prison, Alex is released, a harmless human being incapable of vicious acts. Soon, however, Alex finds he’s not only harmless but also defenseless, as his earlier victims begin to take revenge on him. His old friend Dim and an old enemy named Billyboy are both police officers now, and they take the opportunity to settle old scores. They drive him to a field in the country, beat him, and leave him in the rain. Looking for charity, Alex wanders to a nearby cottage and knocks on the door, begging for help. The man living there lets him in and gives him food and a room for the night. Alex recognizes him from two years ago as the man whose wife he raped, but the man does not recognize Alex, who wore a mask that night. Alex learns later in the night that the man’s wife died of shock shortly after being raped.

This man, F. Alexander, is a political dissident. When he hears Alex’s story, he thinks he can use Alex to incite public outrage against the State. He and three of his colleagues develop a plan for Alex to make several public appearances. Alex, however, is tired of being exploited for other people’s schemes. He berates the men in nadsat, which arouses the suspicion of F. Alexander, who still remembers the strange language spoken by the teenagers who raped his wife. Based on F. Alexander’s suspicion, the men change their plans. They lock Alex in an apartment and blast classical music through the wall, hoping to drive Alex to suicide so they can blame the government.

Alex does, in fact, hurl himself out of an attic window, but the fall doesn’t kill him. While he lies in the hospital, unconscious, a political struggle ensues, but the current administration survives. State doctors undo Ludovico’s Technique and restore Alex’s old vicious self in exchange for Alex’s endorsement. Back to normal, Alex assembles a new gang and engages in the same behavior as he did before prison, but he soon begins to tire of a life of violence. After running into his old friend Pete, who is now married and living a normal life, Alex decides that such a life is what he wants for himself. His final thoughts are of his future son.''

THEMES, SYMBOLS AND MOTIFS

The Inviolability of Free Will

More than anything, Burgess believed that “the freedom to choose is the big human attribute,” meaning that the presence of moral choice ultimately distinguishes human beings from machines or lower animals. This belief provides the central argument of A Clockwork Orange, where Alex asserts his free will by choosing a course of wickedness, only to be subsequently robbed of his self-determination by the government. In making Alex—a criminal guilty of violence, rape, and theft—the hero of the novel, Burgess argues that humanity must, at all costs, insist that individuals be allowed to make their own moral choices, even if that freedom results in depravity. When the State removes Alex’s power to choose his own moral course of action, Alex becomes nothing more than a thing. A human being’s legitimacy as a moral agent is predicated on the notion that good and evil exist as separate, equally valid choices. Without evil as a valid option, the choice to be good becomes nothing more than an empty, meaningless gesture.

The novel’s treatment of this theme includes, but is not limited to, the presentation of a Christian conception of morality. The chaplain, the novel’s clearest advocate for Christian morals, addresses the dangers of Alex’s “Reclamation Treatment” when he tells Alex that “goodness is something chosen. When a man cannot choose he ceases to be a man.” F. Alexander echoes this sentiment, albeit from a different philosophical standpoint, when he tells Alex that the treatment has “turned [him] into something other a human being. [He has] no power of choice any longer.” Burgess’s novel ultimately supports this conception of morality as a matter of choice and determination and argues that good behavior is meaningless if one does not actively choose goodness.

The Inherent Evil of Government

Just as A Clockwork Orange champions free will, it deplores the institution of government, which systematically seeks to suppress the individual in favor of the collective, or the state. Alex articulates this notion when he contends, in Part One, Chapter 4, that modern history is the story of individuals fighting against large, repressive government “machines.” As we see in A Clockwork Orange, the State is prepared to employ any means necessary to ensure its survival. Using technological innovation, mass-market culture, and the threat of violence, among other strategies, the State seeks to control Alex and his fellow citizens, who are least dangerous when they are most predictable. The State also does not tolerate dissent. Once technology helps to clear its prisons by making hardened criminals harmless, the State begins incarcerating dissidents, like F. Alexander, who aim to rouse public opinion against it and thus threaten its stability.

The Necessity of Commitment in Life

Burgess saw apathy and neutrality as two of the greatest sins of postwar England, and these qualities abound in A Clockwork Orange. Burgess satirizes them heavily, especially in his depiction of Alex’s parents. Fearful of going outside and content to be lulled to sleep by a worldcast program, Alex’s parents exemplify what Burgess saw as the essentially torpid nature of middle-class citizens. Conversely, Burgess makes Alex, whose proactive dedication to the pursuit of pleasure causes great suffering, the hero of his novel. Alex himself seems disgusted by neutrality, which he sees as a function of “thingness,” or inhumanity.

“Duality as the Ultimate Reality”

Coined by Burgess in an interview, this phrase reflects Burgess’s understanding of the world as a set of fundamental and coequal oppositions of forces. A Clockwork Orange abounds with dualities: good versus evil, commitment versus neutrality, man versus machine, man versus government, youth versus maturity, and intellect versus intuition, to name some of the most prominent ones. The important aspect of this theme is that, while one element of a given duality may be preferable to the other—such as good over evil—each force is equally essential in explaining the dynamics of the world. To know one of the opposing forces is to implicitly know the other. The notion of duality comes into play in A Clockwork Orangeparticularly during the debate over good and evil, where Alex at one point debunks the validity of a political institution that does not account for individual evil as a naturally occurring phenomenon.

Motifs

Motifs are recurring structures, contrasts, or literary devices that can help to develop and inform the text’s major themes.

Nadsat

Nadsat is the single most striking literary device that Burgess employs. An invented slang that incorporates mostly Russian and Cockney English, Alex uses nadsat to describe the world of A Clockwork Orange. Its initial effect is one of exclusion and alienation, as the reader actively deals with the foreignness of Alex’s speech. This effect is important because it keeps us removed from the intensely brutal violence that Alex perpetrates. Before we can evaluate Alex’s character, we must first come to identify with him on his terms: to “speak his language,” literally. In this way, Alex implicates us in the remorseless violence he commits throughout most of Part One, and we in turn develop sympathy for him as our narrator. In some sense, then, nadsat is a form of brainwashing—as we develop this new vocabulary, it subtly changes the ways we think about things. Nadsat shows the subtle, subliminal ways that language can control others. As the popular idiom of the teenager,nadsat seems to enter the collective consciousness on a subcultural level, a notion that hints at an undercurrent of burgeoning repression.

Nadsat’s origins also help to illuminate the world that Burgess chooses to depict in the novel. The combination of Russian and English indicates that Alex’s society is inspired by the two major superpowers of Burgess’s time, American capitalist democracy and Soviet Communism, suggesting that the two entities are not as far apart from one another as we might have thought.

Classical Music

Classical music enters A Clockwork Orange on a number of levels. On the formal level, the structure of the novel is patterned after musical forms. The novel, which is divided into three parts of seven chapters each, assumes an ABA form, analogous to an operatic aria. Accordingly, Parts 1 and 3 are mirror images of each other, while Part Two is substantially different. The A sections both take place on the streets near Alex’s home and in a country cottage, while the B section takes place in a jail. The A sections begin with Alex asking himself “What’s it going to be then, eh?” The B section begins with the same question, but this time, the prison chaplain asks the question to Alex. The A sections identify Alex by name, while the B section identifies him by number. Additionally, the A sections, as mirror images of each other, feature inversions of the same plot. Whereas, in Part One, Alex preys on unwitting and unwilling victims, in Part Three those same victims wittingly and willingly prey on him. These formal symmetries help us to make comparisons as the thematic material develops over the course of the novel.

On a textual level, Burgess studs the novel with repeated phrases, a very common feature of classical music. Alex supplies these linguistic motifs when he howls “out out out out” to his friends, or tells us that “it was a flip dark chill winter evening though dry,” or when he begins the book’s three parts—as well as the final chapter—with the question “What’s it going to be then, eh?” Burgess was unique as a writer, in that he aspired to adapt the forms of classical music in his writing. His novel Napoleon Symphony derives its structure from Beethoven’s Third Symphony, which was initially written for Napoleon.

Classical music also enters A Clockwork Orange on a narrative and thematic level. Though Burgess probably did not intend it to, Alex’s love of classical music within the confines of the novel’s repressive government invokes Plato, who argued that the enjoyment of music must be suppressed if social order is to be preserved. Plato identifies music with revolutionary pleasure, an association that may easily be applied to Alex in A Clockwork Orange. Alex’s love of classical music is inextricable from his love of violence, and he rarely thinks of one without the other. Both of these passions fly in the face of a government that, above all else, desires a Platonic order. It is thus no accident that Alex’s taste for Beethoven and Mozart sours once he undergoes Reclamation Treatment.

Christ

The repeated references to Christ serve two functions in the novel. First, they provide a structural and thematic analogy for Alex’s life. Alex is a martyr figure who gives up his individual identity for the citizens of his society. His attempted suicide in the last third of the book works as a sacrifice that exposes the repressive State’s evils. In addition, Alex’s narrative goes through a succession of three stages that invoke Christ’s three final days. As Jesus dies, is buried, and is resurrected on the third day, Alex gets caught, is buried in prison, and returns to his former self by the end of the novel. Alex occasionally alludes to Christ, such as when he refers to himself as a Christ figure in Part One, calling himself the “fruit of [his mother’s] womb,” and again in Part Two, when he mentions turning the other cheek after being punched in the face. Second, the repeated Christ references subtly insinuate that the State is using Alex’s violent impulses against him. Alex’s impulse toward violence twice leads him to identify with the Romans who torture and crucify Christ. In this way, Alex unwittingly aligns himself with the State, since the Romans who crucified Christ were, in effect, the “State” of biblical times.

Symbols

Symbols are objects, characters, figures, or colors used to represent abstract ideas or concepts.

Milk

As a substance that primarily nourishes young animals, milk symbolizes the immaturity and passivity of the people who habitually drink it at the Korova Milkbar. Their drinking of milk suggests the infantilization and subsequent helplessness of the State’s citizens. By virtue of its whiteness and homogenization, milk also symbolizes uniformity among the teenagers who drink it. The fact that the milk is laced with drugs is ironic, suggesting that these youths are less wholesome and innocent than adults, not more.

Drencrom, Vellocet, and Synthemesc

Referred to generically as hallucinogens in this study guide, these three drugs symbolize neutrality, or “thingness.” The people in the novel who use them become inhuman while experiencing the effects of them, receding from the reality around them.

Images of Darkness, Night, and the Moon

These things are associated with Alex’s domain, and thus represent peace and security to him. The chaplain, who is garbed in black and defends Alex against the State, might also fall into this category of objects. Darkness represents the privacy and solitude necessary for an individual will to exist and make choices freely.

Images of Lightness and Day

Daytime and sunlight represent danger for Alex. In Part One, Alex notes that there are several more policemen—figures of repression—out patrolling during the day. The harsh lights of the police station interrogation room create a kind of artificial day, and the doctors, with their white jackets, continue the trend of brightness being associated with threat and menace. The only time the chaplain wears white is during an exchange with Alex, where the chaplain gets Alex to snitch on his fellow prisoners in order to further his own career ambitions. Lightness represents the demystification of the individual.

- SPARKNOTES (http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/clockworkorange/themes.html)

RELATED IMAGERY - AKA THINGS TO STAY AWAY FROM (to avoid a cliched design)

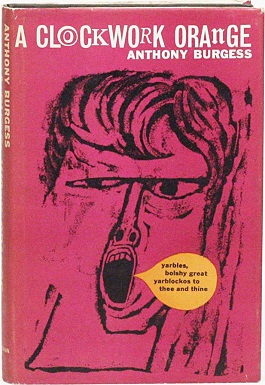

This famous cover is widely regarded as one of the best covers of all time, however I really don't see why. I find the illustration poor quality, and the use of bright colours looks childish, not communicating what the book is about at all.

This is much more communicative of the themes the book explores, with the lino print looking distressed and disturbing, the red evoking anger and thoughts of blood. I don't however like the speech bubble, which is in too different a style than the rest of the illustration.

I want to stay away from cliched imagery such as the eyelashes, eyes and Alex. The ransom-note style typography on the last image is very interesting and could be explored further, however I dislike the imagery which looks too tatty for a modern print of the book. I also wanted to avoid using orange as the main colour as I felt that it was too obvious a design choice, regardless of how relevant it is.

Punk aesthetics are relevant thanks to their anti-establishment attitude and connotations to rebellion

Heavy black type and images look sinister and dangerous, which would definitely be applicable to the clockwork orange cover.

One of my favourite covers is for LOTR. It's beautiful foil finish and matte stock give it a rich and luxurious aesthetic, with the imagery being relatively simple, but plot relevant. The typography is very readable, sampling the gold colour for the subtitle. Something that this cover doesn't deal with however that I will have to, is a quote and the 'penguin books' logo. Having a quote on the front of the book is something I really hate as it breaks immersion so much. The cover shouldn't have to advertise the book- I don't think anyone buys a book in this way, they usually know about the book prior, or become interested by the blurb.

THOUGHT: the movie is world famous nowadays, and is most likely the reason why anyone would read the book, however the movie has some visuals which are not spoken about in the book. Would using these visuals on the cover be an error or not? I think it would be fine to do so thanks to how famous the movie is, but I am going to avoid it, as once the book has been read, the reader will undoubtedly question the imagery.

Current favourite book covers

The use of colour, negativ space and simplicity here is fantastic, no element can be taken away without ruining the design- showing how refined the idea is. The serif compliments the sans-serif, as does the contrast in line weight. The bright yellow connotes happiness and sunshine- themes within the book, whilst the arc of the type obviously suggests a frown, contrasting again with the bright yellow.

This non-fiction book on the columbine massacre uses a standard photograph, exploiting the grey sky to represent an ominous and gloomy atmosphere. The white helvetica type looks dead and emotionless.

Here the coathanger makes the audience think about self-worth, with the sexual imagery conjuring thoughts of human nature and the way we look at ourselves and each other. The orange dress fits nicely, using the same colour as the penguin logo. The typewriter font gives it a personal and dated aesthetic.

The simple use of type as image here is brilliant, as is the use of negative space in the chair. The gold colour communicates weath as does the simple elegant illustration and art-deco style font. This cover perfectly shows how powerful good typography is at communicating themes.

This cover for The stranger gives a sense of height and vertigo just through these violent and jagged lines. The simple type gives nothing away, making the text 'the stranger' a mystery- conceptually linking to the books character. The black and white colour scheme also give no extra connotations making the cover a mystery to be decoded by reading the book.

I would like my cover to be influenced by these - I want the reader at certain intervals to go 'so that's why the cover has this element' etc.

I watched a documentary whilst researching for this project called 'The mind of a murderer'. Alex in clockwork orange murders and rapes multiple people, so I wanted to know what it was like inside his head. The psychologists examined and questioned multiple murderers, assessing that the mind of a psychopath/sociopath is fragmented, the ability to compartmentalise different emotions and memories removes empathy and can damage their ability to create proper relationships.

This fragmented and compartmentalised mind could be visualized with broken graphics, an ecclectic use of type (as if the brain can't remember the same typeface twice), or distorted and warped graphics.

Concepts: anarchy/chaos within systems/confinement (playing on the murderer's mind research). This is displayed through taking single letters from different typefaces (being taken from their natural environment, as Alex was). The orange O is representing the physical orange, as well as an eye on the back page.

I added a white boundary around the type, the idea being that the letters are in confinement with others not like it. I chose futura condensed for the blurb again running with the idea of pressure and confinement. The type is still very readable. I changed the line 'but at what cost' to the orange used through-out to emphasize the importance of it, the effects of Alex's incarceration being paramount. The boundary plus the removal of some of the elements gave room for the quote.

I lightened the black to (4,0,0,95) as I felt that the original black was too contrasting to the white type and needed softening slightly. The type is now easier to read also.

Final

In this final design, the dark watch mechanics in the background would be gloss whilst the rest of the design would be matte.

I am still somewhat unsure about the type on the blurb. I felt that transitioning from a complex and fragmented front cover to a necessary legible back may break immersion, so I carried the clockwork imagery onto the back, and used the same typeface I used for the quote. If I had more time with this project, I would experiment more with deconstructing the blurb's type and seeing how far I can take it before it becomes too illegible to function.